In honor of #PrideMonth, Nintendo Power reporter Devin Blake-Newman spoke with the original creative team of Super Mario Kart (SNES, 1992) about the game’s unusual genesis and legacy, but more importantly that of its groundbreaking gay-themed level: Rainbow Road. Interviews have been lightly edited for clarity.

TADASHI SUGIYAMA, DIRECTOR: Super Mario World (SNES, 1990) had just been released to much fanfare and we were all celebratory, of course, but quickly intimidated by that age-old question: what next? Miyamoto-San [Shigeru Miyamoto; producer, Super Mario World] had some ideas that many of us at Nintendo were struggling to get on board with.

HIDDEKI KONO, DIRECTOR: Miyamoto had always been very drawn to… unique themes. For instance, when we were developing the very first Mario game [Super Mario Bros., NES 1985], he would ask if we had “perfected the kissing mechanic.” The design team was quite confused. He explained to us that at the end of the game he wanted Mario to kiss Bowser. “Mario must unite with his enemy,” he would say. The technology at the time wasn’t capable of rendering this to our satisfaction.

SHIGERU MIYAMOTO, PRODUCER: I myself am not gay. I know there is some confusion on this point. I am straight. But yes, I have always aimed for Nintendo to be a “paint with all colors” company--

KONO: “Paint with all colors” was the direct inspiration for Mario Paint (SNES 1992), which was originally going to have a Keith Haring level.

MIYAMOTO: —one where, if we had the technological capability, we should be using it to promote tolerance and allyship. If that is “gay,” then fine — I guess I am “gay.”

KONO: It was a noble mission to be sure but the game ideas that came out of our first brainstorm sessions were not feasible for technological or cultural reasons. For many weeks Miyamoto demanded we rough out an action-adventure game called “Harvey Milk and the Quest for Dignity,” which would have ultimately been similar to The Legend of Zelda, but set in 1970s San Francisco. Rendering Castro Street to Miyamoto’s liking proved impossible.

SUGIYAMA: “Super Stephen Sondheim’s Follies,” that was another one he seemed very intent on. Did we think it would sell? Perhaps. Miyamoto is a genius. But with each of these new game ideas, he eventually came to realize they were all pipe dreams. (a beat) That is some Mario humor for you. He travels through many pipes.

KONO: We devoted three months on “Follies” before Miyamoto finally conceded it could not be done, or as he put it—

MIYAMOTO: The world was not ready.

KONO: This string of cancelled projects returned us exactly to where we had started, still in want of our next SNES title. Can you be a game company that does not make games? Existentialism blanketed our break room conversations like a… very big blanket indeed. Like a blanket for a giant or some other large creature.

SUGIYAMA: Then Hinata Saito came onboard, which of course changed everything.

HINATA SAITO, PRODUCTION ASSISTANT: My mother worked in accounting and had helped Nintendo fudge sales numbers for R.O.B. [Robotic Operating Buddy, 1985] when that venture proved unsuccessful. They owed her a favor, which she utilized to procure me a job. Mostly I got coffee for the SNES development team, which I liked, and answered all of Miyamoto-San’s questions about being gay, which struck me as off-topic.

KONO: Miyamoto was obsessed with Saito. Most mornings we didn’t start work until 11:30am, noon because he was peppering our new assistant with questions. “What establishments did you frequent last night?” “Was there dancing?”

SUGIYAMA: “How fashionable were the boys?” And so on.

MIYAMOTO: Creativity necessitates curiosity. Questions are the lifeblood of art. I do not know why we are even talking about this.

SAITO: The questions didn’t bother me. Miyamoto-San was clearly… curious about certain things, and even if it had nothing to do with game development, it was better than assisting my mother in the accounting department.

KONO: Saito would frequently come to work wearing sunglasses, which Sugiyama and myself knew to mean he was trying to hide a hungover but Miyamoto thought was the height of contemporary style. Miyamoto started wearing sunglasses too. “Hey, cool guy!” He would say. “I’m joining you on the cool guy train.”

SUGIYAMA: All the while, the Nintendo board was demanding we present a new game, and we were no closer to even the most rudimentary idea. We had merely a Post-It that read “cool guy train.” Kono and I tried to impress upon Miyamoto the importance of staying on task.

KONO: At these junctures, he would often lower his sunglasses down to the bridge of his nose and say, “Don’t have a cow, man!” Then he’d flash this look to Saito as if to say “these guys, right?” The whole team was dangerously close to being terminated.

SAITO: I look back on this as a great and memorable time in my life. Every night I would party and rather than suffer the consequences of it the next day, I was treated like an essential member of the team. Miyamoto even gave me his parking spot.

SUGIYAMA: One morning, Saito showed up especially late. Miyamoto peppered him with the usual questions: “How many sea breeze cocktails did you drink? Did they taste good? How many calories did they contain?”

MIYAMOTO: Unless I am mistaken, watching your weight is not a crime in Tokyo. Certainly it was not in 1991.

SUGIYAMA: Sensing another day’s work already lost, I had started drafting a query letter to the Sega Corporation. But then something in Saito’s response caught my attention. Caught all our attention.

KONO: Rainbow Road. That was the morning he pitched Rainbow Road.

SAITO: Even today I do not understand what came over me. Perhaps I was still drunk? I wanted to have some fun with Miyamoto-San, so I... just started saying things.

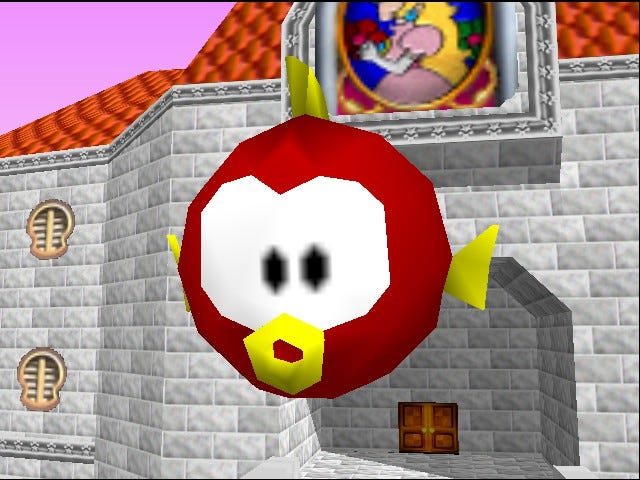

MIYAMOTO: Saito spoke with candor and poetry of somewhere in Tokyo I’d never heard of, a night market criss-crossed by alleys of red, orange, green — all the colors of the rainbow. These alleys were so wide that several velotaxis could drive side-by-side, their drivers hawking mushrooms and bananas at passersby, all men, who ate them with abandon.

SUGIYAMA: It was quite clear to Kono and myself that everything Saito spoke of was a fiction, that no such night market existed. Vending machines doling out shells and glowing stars? Still, Miyamoto was mesmerized.

MIYAMOTO: I was mesmerized.

SAITO: Miyamoto-San had lowered his sunglasses, which meant I had his attention. I felt emboldened to weave an even more outlandish tapestry: men in overalls mingling with men dressed as giant turtles, racing velotaxis from bar to bar, exciting one another with their speed.

MIYAMOTO: And finally, the grace note.

SAITO: …I told him that for some reason there was also a giant fish blimp suspended in the air. I could have said anything at that point.

KONO: The room fell silent. Miyamoto stared at Saito for what felt like five minutes, then ordered me to bring him a pad of paper and some colored pencils, which we kept in a Yoshi-shaped desk in the corner. I obliged. First he began to sketch. Then he started talking, as though the words were already written in his memory.

SUGIYAMA: “The game is called Super Mario Kart. Eight characters from the Mario series race one another on courses both familiar and brand-new. Speed through them using power-ups like mushrooms and invincibility stars…”

KONO: “…or fall prey to weapons like homing turtle shells and banana peels. Victory is a matter of both skill, and luck.”

SUGIYAMA: Miyamoto spoke for a full hour and outlined every mechanic of the game we’d release one year later, including Time Trial and Battle modes. We changed literally nothing from his original, completely extemporaneous pitch.

KONO: I can recall word-for-word just two moments from my life: what my father said to me on his deathbed, and the conclusion of Miyamoto’s speech. “After fifteen levels of intense competition, the quest for racing mastery will end with one final course, a spare but graphic tribute to the vibrant gay culture of Tokyo.” That’s when he showed us what he’d been sketching the whole time.

MIYAMOTO: Rainbow Road.

KONO: All those seemingly wasted months, all the aborted games, all the pairs of sunglasses — somehow they’d been transformed into this one crucial moment of genius.

SUGIYAMA: We knew then that the Super Nintendo would be saved, and I would not be transferring to Sega. Sorry, Sonic! (laughs) But I think for Miyamoto this represented much more.

KONO: Development came together very quickly after that. One team oversaw the racer physics, another the courses. Miyamoto insisted on programming the Rainbow Road course himself.

SAITO: After the meeting, Miyamoto asked if I’d show him the “real Rainbow Road,” for inspiration. I confided in him I’d had too many drinks to remember exactly where in the city it was. “Someday,” he said.

MIYAMOTO: I did say that, I said “someday.” I remember everything I’ve ever said.

SAITO: He’d call me every so often about it; I’d always feign an excuse. Eventually I told him the night market was bulldozed to make way for a Uniqlo. Almost thirty years later, the whole still boggles my mind: I drunkenly fabricated a tale of gay turtle-men and speeding velotaxis and rainbow alleyways and now… it’s a videogame. Crazy.

MIYAMOTO: I am not a fool. I know there was no actual Rainbow Road, that it was a fiction concocted by Saito. But the story was so nice. I’m glad Nintendo fans get to visit some version of a place that even today still means very much to me.